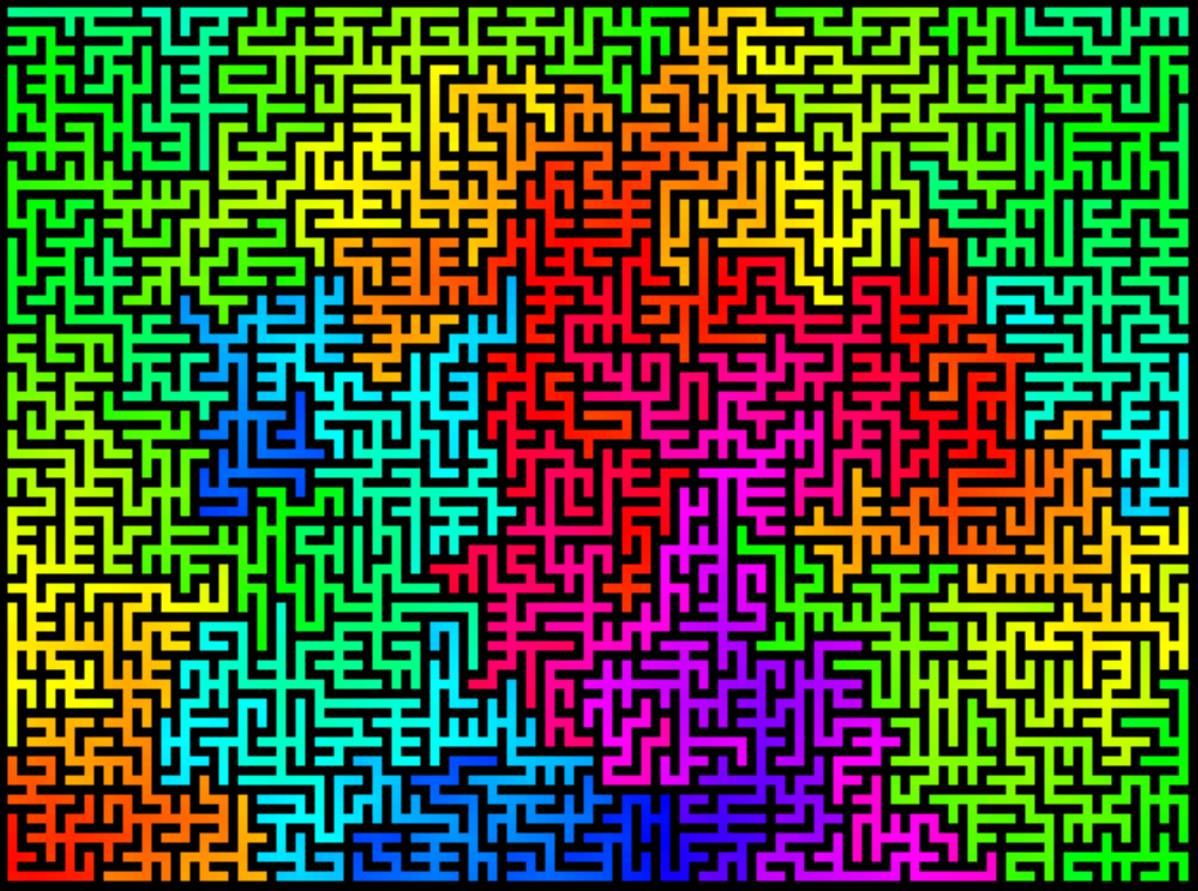

White Nightmare

When I was a child, I used to have a recurrent nightmare. Now I have recreated it with code.

The story

Note This is the translation of the original story I wrote in Spanish. You can find the Spanish version here.

I do not remember my own dreams anymore. I only wake up to feel the last shreds of a dream tangling around my pillow, and then I try to munch out its aftertaste while I rouse myself, until it finally vanishes away. Whether that taste is bitter or sweet, it is up to each dream, but they all end up fading out of my memory anyway. There are, however, some recurrent childhood dreams from which I still keep a vivid image.

Almost all these recurrent dreams were nightmares, most of them ridiculously naive and harmless when thinking retrospectively. Maybe some spooky monster here and there, or images from a horror movie trailer I should not have watched… The usual stuff kids experience at that age. One of them was, nevertheless, particularly haunting, and still nowadays it makes me admire the psyche of my inner pants-shitting ten-year-old. There are no monsters in that dream, nor blood or any definite dangers. I cannot even say whether a single person I know shows up there. I do think I am present, even though that presence is intangible, incorporeal, almost indescribable.

Let me try to explain it: This nightmare looks like a fuzzy frame of white noise, this kind of snowy mess you can see on the screen of an old untuned TV. The main difference is the noise pattern, which stretches across fixed lines as a maze does. It actually IS a maze, and I am staring at it from above, like from a bird’s eye view. Sound plays a role in this dream too, and it also resembles the crackle of an analog TV. These are all the sensorial details I can provide, as the terror of this white-noise nightmare lies much more on the sensations it conveys. Should I fix my attention on one of the lines, an intuition will rapidly come through to persuade me I am lost in it, buried so deep down in that trench that I can barely see myself. And then the sound rises up to a deafening volume, while the image convulses furiously. The evidence of confinement grips me tighter and tighter in this abstract corner of the labyrinth. My family and friends may be hidden in another unreachable region of this black-and-white map. The experience is probably also unpleasant for them, but they are at least together. Unlike them, I am fully isolated, dozens of pixels away from my loved ones. And I ignore whether they miss me, or if they are worried, or trying to find me by any means…

There is no further development of the dream. The sensations I have described just keep building up in a cruel crescendo until anxiety grows unbearable. On the edge of a child’s psychological pain threshold, I suddenly wake up. The deafening white noise starts to settle down, like venomous sea foam that retires from the skin without moistening it. It will still take one or two minutes to untie the knot in my stomach.

The math

The nature of the nightmare, based on this concept of a maze emerging out of white noise, lends itself to a quite clean mathematical model. I just needed a couple of ingredients to put it together nicely:

- A maze generation algorithm.

- Some statistical tools to mimic the noisy effects, most of which are related to autoregressive models.

Both concepts sink their roots into probability theory. This means that they operate randomly according to some probability distribution: with every run of the algorithm you generate a unique, distinct maze. Likewise, every time I simulate my nightmare it will be similar but subtly different. That is exactly the way it would also happen during my childhood, every four or five months the same vibes to different pictures.

Maze generation

There is a bunch of algorithms to generate mazes out there, those based on graph theory being my absolute favorite. Under this setup, the maze is modelled as a graph where nodes represent cells and edges represent walls, and the task consists in finding a spanning tree for that model.

For this project I chose Wilson’s algorithm, which generates very esthetically pleasant mazes in an unbiased way. A big source of inspiration here were Mike Bostock’s examples. Make sure to check them out to learn more about this algorithm.

White noise

All Wilson’s algorithm returns is an abstract graph of cells and walls. In order to accommodate it in between the white-noise jungle, we need to render it, and we better make it look like proper white noise.

Signal theory defines white noise as a random signal whose frequency spectrum is flat. This means that they are composed of all frequencies of the spectrum, in the same way that white light comprises all frequencies in the visible spectrum (what we actually know as colors), hence the name. A consequence of it is that all signal values are independent of each other. These values often follow a Gaussian distribution, although this is not always the case.

Autoregressive models

The grayscale levels of the cells and walls in the maze cannot be independent random values, otherwise the structure would be lost. On the other hand, if we naively assign black level to walls and white level to cells this will stand out of the white noise and the visual impact will be equally lost.

The solution is to find a trade-off: the brightness of the pixels will be random, but somehow similar to their neighbor’s, so that the structure is preserved. That is what autoregressive models are about.

Autoregressive models (AR models for short) are random processes obtained by weighting and averaging a random value with some of the previously calculated values of the process. Under the right parameters it has a smoothing effect: values are arbitrary, but they do not deviate wildly from their neighboring values.

The model I chose is a variation of an AR(1) process, meaning that I only take into consideration a single past value. It is really as simple as it gets:

\[X_t=\alpha X_{t-1}+\left(1-\alpha\right)\epsilon_t\]where \(\epsilon_t\) represents an (independent) random value, \(X_{t-1}\) and \(X_t\) are the values of the AR model for positions \(t-1\) and \(t\) respectively, and \(\alpha\in\left(0,1\right)\) is a smoothing factor: the closer \(\alpha\) is to 1, the more similar \(X_t\) will be to \(X_{t-1}\).

I apply this AR model along the path, in the same direction as the color gradient above. The only difference I make between walls and cells is in \(\epsilon_t\); in the case of cells, I draw it from a Gaussian distribution centered around a bright value, while for the walls the center of this distribution is dark.

But this is not all. Walls and cells have a certain width, so they cannot be as granular as proper white noise. In order to overcome this, I apply fine-grained white noise on top of the AR maze, making it indeed look noisier.

Note As a matter of fact, video coding standards wildly reduce such high-res features. That is the reason the GIF and the pictures exhibit more granularity that the video on top of the page.

You may have noticed that the maze pattern does not stay still, but it rather keeps shaking around timidly. Can you guess how I model this random shift? You are right: Autoregression.

In that case I calculate two different AR processes: one for the column shift and another one for the row shift. Then I apply this \(\alpha\)-smoothing along the corresponding direction, so that two consecutive rows/columns are not abruptly shifted apart from each other. On top of that, I also smooth it down along the time direction to avoid extremely fast changes.

How white is your noise?

This is a bonus for signal-theory lovers. I have to reckon I have cheated: I keep talking about white noise while the background of the image is everything but white noise. This is how Gaussian white noise looks like for a certain picture width and height:

While the actual background of the animation would be something like this for the same dimensions:

I am sure you can spot the difference. This is even easier to see if we take a look into the frequency spectrum:

The frequency response of pure white noise is clearly flat at around -27 dB (as this is one of its properties). On the other hand, the noise background I generate has a -16 dB plateau from -0.125 to 0.125 cycles/pixel (for both vertical and horizontal frequency axes) on top of a -31 dB floor. It is, thus, not flat, and so it is neither white.

The reason why I painted the background with colored (a.k.a non-white) noise has to do with the maze. Here you can see its frequency response:

It is definitely not flat either. Furthermore, it also exhibits the same low-frequency plateau and high-frequency floor as the background, plus some shiny edges at the transitions and some ripples in between. That is the trick: ripples and edges account for the maze structure, the central plateau represents low-resolution details (the thick walls and cells), and the floor represents fine-grained noise, that is, high-resolution details (which are encoded at higher frequencies).

The background is some “quasi-white noise” that mimics the maze. I create it by generating coarse white noise, zooming in and adding finer white noise on top. That is why its frequency response looks similar as the maze’s does.

But not only they look similar in the frequency spectrum. Here it is a comparison of a half-emerged maze against the actual background vs. the same rendering against pure white noise:

Do you notice? If I used pure white noise for the background, the animation would look patchy instead of smooth.

Background and maze do have a similarity with pure Gaussian white noise, though. It unveils itself if we look at their histograms:

They are actually very similar! Here you have an example how the histogram of a stochastic signal does not say anything about its frequency response, and vice-versa. This is a very common pitfall among undergraduate and graduate engineering students, including myself.

Disclaimer The histogram of maze and background is not Gaussian strictly speaking, but a mixture of two Gaussian curves (one for walls and another for cells) lying so close together that appear as a single one in the histogram. This is also why there is a notch between the dashed Gaussian fit and the actual count bins, as their distribution is slightly broader. This comment is irrelevant for the sake of the discussion, anyway.